LET’S TEST YOUR MIND!

Quiz

Quiz

Adjit (adj) means...

Having a strong feeling to fight oppression (– shortened word for ―agitated)

ED and GD (n) are abbreviations for?

Educational Discussion; also GD stands for ―Group Discussion; refers to activists study of the system/society

Alias means/refers to...?

Made up and/or symbolic names

Used by activists to avoid being identified and arrested, for example Amado Guerrero (Jose Maria Sison) and Ruben Cuevas (Pete Lacaba)

GD or GND is an abbreviation for

Refers to an activist who adheres strongly to his/her ideology; a person who does not show happiness

Imeldific means

The word was coined after former Philippine first lady Imelda Marcos to mean ostentatious extravagance

Jeproks refers to –

Refers to apathetic, hipster, uber-laid back young person

Derived from the word ―project; referring to people living in the urban/middle-upper class areas of Quezon City, Projects(village) 1-8

Refers to a group with strong ties; persons belonging to the same batch of recruits to the movement

Kolektib

Refers to the first air conditioned buses in Manila that made a loop from Cubao to Makati to Escolta

Love Bus

Activists who believe that oppressive society/system can only be transformed through armed struggle

ND /NatDem (n) – short for National Democrats

A nutrient fortified sweet roll developed in the early 70‘s by USAID in the Philippines to feed students in public schools

Nutribun or Nutrition Bun

A practice to ensure that one is not being followed to the safe house/underground house

Pagpag

Originally means to save or to rescue

Salvage used as a euphemism ― to execute extra-judicially

Refers to the discovery of a safe house which could lead to another safe house

Sunog

SD/SocDem – short for Socialist Democrats refers to

Activists who believe that changing the oppressive society/system can be achieved through peaceful means

Tibak is or is derived from

Aktibista or activists

Refers to the surveillance of the military; in Filipino folklore, refers to a creature that prowls at night looking for houses with pregnant women to feast on their babies.

Tiktik

UG is abbreviation for ―

A place beyond the reach of the legal system

Noong panahaon ni Marcos, 2 to 1 ang palitan ng Philippine peso to US dollar. (True or false)

False

The exchange rate between Philippine Peso and US dollar in 1965 was pegged at 3.9 pesos to 1 US dollar. And 18.6 to 1 US dollar in 1985 (Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas)

Maunlad ang ekonomiya (golden age of economy) Pilipinas noong panahon ni Marcos. (True or False)

False

Economic indicators such as GDP tell the opposite (See the next feature for the graph). In fact, unemployment rate ballooned from 7.20% in 1965 to 12.60% in 1985 (PSA and Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas).

Madaming napatayo si Marcos na mga gusali na papakinabangan pa ngayon. (True or False)

True

We cannot deny that the regime was able to build establishments, buildings, and bridges for 20 years in power (equal to 3-4 presidents in the current constitution). However, it must be clarified the funds used were not from the Marcos. These came from Filipino taxpayers and from external debt. Because of this, Philippine External Debt rose from $360 million (US) in 1962 to $28.3 billion in 1986 (Boyce, 1993). Filipino people are still paying for this debt up until now.

Walang Human Rights Violations noong panahon ni Marcos. (True or False)

False

(See the panels for complete details)

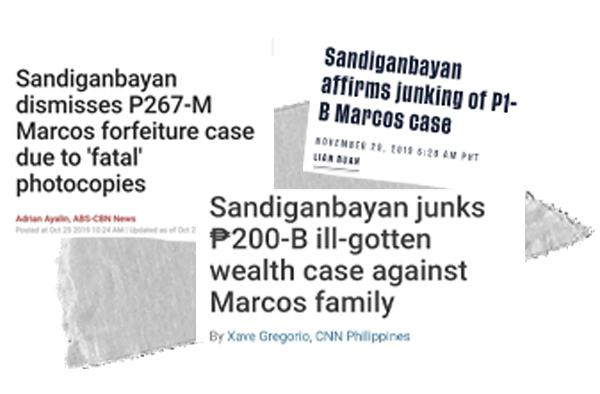

Hindi naman naconvict o wala namang napatotoohanan na nagnakaw ang mga Marcoses (True or false)

False

There are certain judicial verdict to prove this claim:

1.) Judicial courts (local and abroad) were able to recover ill-gotten wealth from the offshore accounts of the Marcoses. This paved the way for the creation of the Human Rights Victims’ Claims Board that aimed to recognize and provide reparation to Martial Law Victims.

2.) Philippine Commission on Good Government, as of April 2019, recovered more than 171 Billion pesos of ill-gotten wealth since its creation in 1986.

The Marcos regime instituted a mandatory youth organization, known as the Kabataang Barangay, which was led by his Marcos‘ eldest daughter Imee.

Presidential Decree 684, enacted in April 1975, required that all youths aged 15 to 18 be shipped off to remote rural indoctrination camps where they underwent a ritualistic progra designed to instill loyalty to the First Couple (McCoy, 2009; Wurfel, 1988)

KB has been abolished under Cory. It was reinstituted in the Local Government Code of1991 as Sanguniang Kabataan (SK).

ARCHIMEDES TRAJANO

Trajano, an engineering student from Mapua Institute of Technology, stood up and did what participants are supposed to do at forums: asked a question to imee marcos who was then the head of kabataang barangay during a forum at the pamantasan ng lungsod ng maynila.

“Must the Kabataang Barangay be headed by the President’s daughter?”

Imee didn’t answer the question. Instead, Trajano was forcibly removed from the premises by her bodyguards, and the student vanished. Two days later, on Sept. 2, his bloodied corpse, bearing signs of severe torture, was found abandoned in the street.

the period of martial law is marked with strong youth movements sdk (samahang demokratiko ng kabataan) and KM (Kabataang makabayan) , along with other youth formations and sectoral movements led the series of youth demonstrators during the time of the first quarter storm (FOS) or SIGWA (RAGE

“I believe our greater responsibility in a crucial time like this, is to seek and know the truth for ourselves as well as for others, because in the language of the gospel, only the truth wil set us free.

The good thing about truth is that no superpower here on earth can bomb the truth or shoot it down”

– JOVITO SALONGA

“And so law in the land died. I grieve for it but i do not despair over it… I know with a certainty, no argument can turn, no wind can shake, that from it, dust wil rise a new and better law; more just, more human, and more humane, when that will happen, i know not. That will happen, i know.”

– JOSE DIOKNO

“Our economy is in shambles and our children are heirs to an almost unbearable national debt because good and decent citizens have abandoned politics to the corrupt.”

– EVELIO JAVIER

It can be said that Marcos built more schools, hospitals, and infrastructure than any of his predecessors combined (Lacsamana, 1990), but this is true given the consideration that Marcos was in power for about 20 years and he had the US in terms of massive economic aid and foreign loans.

The peso devalued from

PhP3.9 to USD1 to PhP18.6 to USD1

from 1965 to 1985 (Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas)

The unemployment rate ballooned

FROM 7.20% IN 1965 TO 12.60%

in 1985 (PSA and Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas)

The Philippines‘ external debt rose from

$360 million (US) in 1962 to $28.3 billion

in 1986, making the Philippines

one of the most indebted countries in Asia

(Boyce, 1993)

In November 18, 2016, Ferdinand Marcos was secretly buried at Libingan Ng Mga Bayani.

Making the Philippines a laughing stock of the whole world by giving a dictator, murderer, and plunderer a hero’s burial.

THE RETURN OF THE MARCOSES TO POWER

Dismissed cases because of PCGG’s and OSG’s lack of due diligence in litigating the cases under the Duterte’s Administration

Political climate may greatly affect how people exact accountability from the Marcoses.

We have observed how the Philippine Commission on Good Governance and the Ofice of the Solicitor General under Duterte’s regime mishandled these cases that led to Marcoses’ acquittal.

” Martial law could crush our bodies; it could break our minds; but it could not conquer our spirit. It may silence our voices and seal our eyes; but it cannot kill our hope nor obliterate our vision. “

” Martial law was a time when so many of the country’s best and the brightest fell into the dark pit of state terrorism. But this was also a time when so many of the country’s best and the brightest rose to remind the world of what it means to be bright enough to become CEO of a good company or succeed abroad, it is to be bright enough to know that you become your best when you serve the people. “

” Forgiveness without truth is an empty ritual and reconciliation without justice is meaningless and, worse, an invitation to more abuses in the future. “

MOVeMENT

SUCCESS

Although it seems we are far from exacting genuine accountability from the Marcoses and his cronies, we cannot but to celebrate our successes in the movement such as